If you’ve ever held a mutual fund, you might have noticed a cash payment show up in your account, or the number of fund units in your portfolio suddenly increase. It’s likely you received a mutual fund distribution, which is essentially a payment of cash into an investment account. Not all mutual funds pay distributions, with some paying annually, quarterly or, like Mawer’s funds, occasionally. But whether you get one or not, it’s a good idea to understand how they work and why they exist, so you can make more informed investment decisions.

What are distributions?

A lot of people think that distributions are the same as dividends, but that’s not so. Typically, companies pay dividends, which is a portion of their earnings to shareholders. Mutual funds pay distributions, which can include all kinds of income, such as interest, dividends, realized capital gains (essentially what a stock makes between the time its bought and sold), a return of capital, withholding taxes and more.

As mentioned, not all mutual funds pay distributions and getting a payment in one year doesn’t mean you’ll get one in another. For instance, funds that invest in dividend-paying stocks do tend to have a payout, but ones that don’t own these kinds of companies may not. As well, whether a fund distributes dollars also has to do with how much tax the fund might have to pay that year.

Why do funds distribute cash?

Funds distribute cash in large part because it’s tax efficient. Mutual funds are considered unit trusts, which are vehicles that can enjoy non-taxable status, but only if they distribute out any earned income and gains within the calendar year. If they don’t, they are taxed and at the highest marginal rate. While investors will need to pay tax on the distributions—even if the money is reinvested —their bill is based on their own marginal rate, which is usually lower than the fund’s rate. In some cases, the investor may not have to pay any tax at all (at least in the year they receive the distribution), this is true if they hold their funds in a registered account such as an RRSP, TFSA, RRIF, or RESP.

What exactly the fund pays out will depend on how much it needs to distribute to remain a non-taxable entity. That number can vary from quarter to quarter or year to year.

Where does the distribution come from?

If the fund is invested in fixed-income instruments such as bonds or the money markets, it will receive interest from its holdings. If it is invested in equities, it may receive dividends. You can get distributions from both. (Note that funds invested in non-income-producing securities may not pay distributions at all.)

Sometimes funds realize capital gains by selling investments for more than they originally paid for them. This may also be distributed to investors. The nature of the underlying investments, then, will affect the level and consistency of the distributions. Some funds will pay out 5% of their net asset value every year; others will pay nothing. The performance of the fund’s holdings may also affect the distribution level unless the fund is structured to maintain a certain payout percentage. (In the case of negative returns, such funds may end up returning invested capital, which is tax exempt.)

How do distributions impact the value of the fund and my investments?

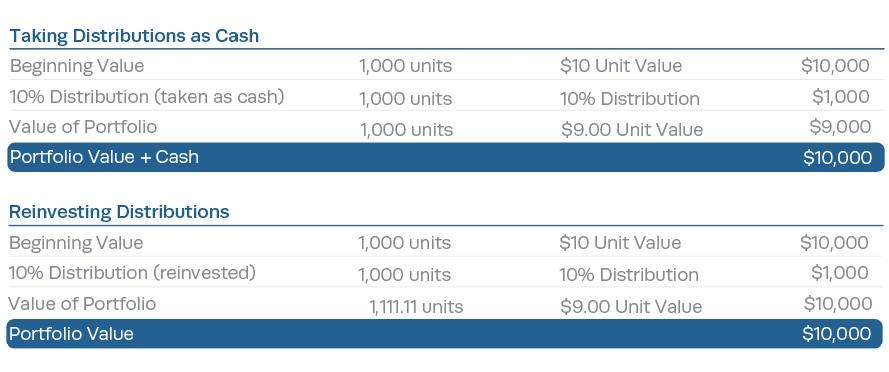

Distributions reduce the net asset value (NAV) of the fund—essentially the value of each unit—by the amount paid out. For instance, a fund might have to pay out 10% of its value because that’s what it earned during the year. When the payout occurs, the fund’s NAV will drop by 10%. (It’s important to note that you might see the drop in the NAV 24 to 48 hours before seeing your cash payment or reinvestment showing up on your account statement. This timing difference will vary depending on which institution you hold your investment account with.)

Don’t worry about the drop in the fund’s value. Firstly, whether you take cash or reinvest, the value of your portfolio remains the same on the day you get your distribution. (See our handy chart below.) Secondly, if you reinvest your cash into more units, you’re now buying in at a lower price point, and you’ll have more units than before. (This could happen several times, depending on how long you hold the fund.)

Hopefully, as the value of the underlying securities rise, the value of your mutual fund investments climbs too. But what happens when it comes time to sell, and you have to pay capital gains on the increase? The reinvested distributions increase your adjusted cost base, which reduces the amount of tax you’ll have to pay when the units are eventually sold.